OA.Works’ Natalia Norori Goes Back to the UN to Talk about Equity and Open

Besides building the tools that make OA.Works work, team Data Wrangler Natalia Norori also uses the tools as she explores research in migration and epidemiology. In this talk at the UN, Norori dives into the difference between open and equitable, using her life experience as a Nicaraguan scientist who has been impacted by migration.

Video

Fast forward to hour 3, minute 35 to see Natalia’s talk.

Slides

Transcript

I was here two years ago, talking about how open science was going to help solve the next pandemic. But I didn’t think the next pandemic would happen so soon.

Today, I’m going to tell you a story about what I knew then, but didn’t say.

And that is that open is not the same as fair. It is not the same as equity.

I think that open science can foster equity when it helps marginalized people learn about and research topics important to them and their communities, have their research recognized and rewarded, and translated into impact for their communities.

These are all big, complex discussions. As they should be. Today though, I’m going to try to keep things simple. Over the next paragraphs, I’ll share my experience of where open science did those things for me, and where it didn’t.

I shouldn’t have to tell you that a huge number of people are traditionally excluded from taking part in research. I am one of those people.

I am currently based in the UK but I was born and raised in Nicaragua, a country with a long history of political repression. The situation back home has not been stable for a while, but the 2018 political crisis made matters worse. The social, economic, and political instability has forced more than 100,000 Nicaraguans to leave the country, producing one of the biggest migratory crises in Latin America history. My mom and dad were part of that wave of migrants. As a result, my family of 5 is now based in 4 different countries.

As a Latina woman who grew up in an unstable environment, I’ve always had questions about what caused it. The social problems I saw demanded answers.

As Nicaragua's regimen started repressing protestors in 2018, I worried about the mental health impact of forced displacement on my friends and family, and I turned to research to learn more about it. But the publishing system was not designed with people like me in mind, and the only way for me to find answers to my questions was through open science. Tools built by organisations like OA.Works helped me get access to research in a broken system. These tools are what allowed me to read papers on migration at a very early stage in my career. Without them, I wouldn't know as much about migration as I do today.

Now, I knew about these tools because I helped build them, but not everyone can find out about them that way. I was able to learn about my interests thanks to people who had previously shared their work openly. I might not have been able to do it otherwise. As part of the OA movement, we need to do a lot more work to get this content into more people’s hands. Even though open science facilitated my research, I could not look beyond what it was allowing me to read, so I still found myself facing many challenges to help solve the issues that were relevant to me.

Today I’m doing an epidemiology course in the middle of the Covid pandemic, but Covid is not my priority. While everyone else is thinking about Covid, I’m still thinking about the problems that affect the places where my family and I have lived and have had ties to for generations.

Migration has huge implications for public health, but the health of migrants has been largely overlooked in research and policy. It also has a strong connection to climate change. It is expected that by 2050, the stock of international migrants worldwide could reach 405 million. Out of those, around 200 million are expected to be displaced by climate change. The migration crisis is one of the biggest human rights issues of our time, yet, very little research has been done in this area. As a migrant, I want to help change that.

For my masters degree dissertation, I’m using open data to look at the impact of paternal emigration on children ‘left-behind’. The Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition survey is a study that has been following a cohort of Filipinas who gave birth between 1983 and 1984 in Cebu, and their offspring. The study was originally conceptualized to understand infant feeding patterns, but thanks to its accessibility, it has been used to study other topics, such as sexual and reproductive health, mental health, and factors associated with the development of NCDs, such as diabetes and heart disease. The Cebu website has identified 257 publications that have used their data, but a google scholar search finds around 681 results. All of these research outputs have been possible because of the efforts of the study organizers, who were pioneers in opening up health data when it was not common to do so.

Without open data, I would not be able to conduct this study. It would not be affordable, and as an early career researcher, it would be hard to get the support I need to help guide my research. I would not be able to access what was previously closed to me, and help to answer the questions I was asking before. Open data makes it possible for me to explore systemic problems in the communities I am from.

That said, I still had to move continents and get scholarships to be able to get the skills and know how to use the data.

I am extremely fortunate to be affiliated to an institution that has the funds to help me overcome the barriers that would have prevented me from having my research read and recognized. I also have access to an institutional repository where I can share my work as soon as it is available. Not many people from my background have this option.

For example, the official journal of the Royal Society of Public Health, one of the most respected journals in my field, has an APC of $2800. For context, the $2800 price tag is 1.3 times higher than Nicaragua’s GNI per capita. The publishing system harms equity by forcing researchers without funding to choose between being seen and being rewarded.

Even though there’s not enough data for me to study the impact of paternal emigration on Nicaraguan children, I can get a lens on it because there is data on The Philippines . By opening up all aspects of my research, I hope to help others get answers to the questions that are important to them and their communities.

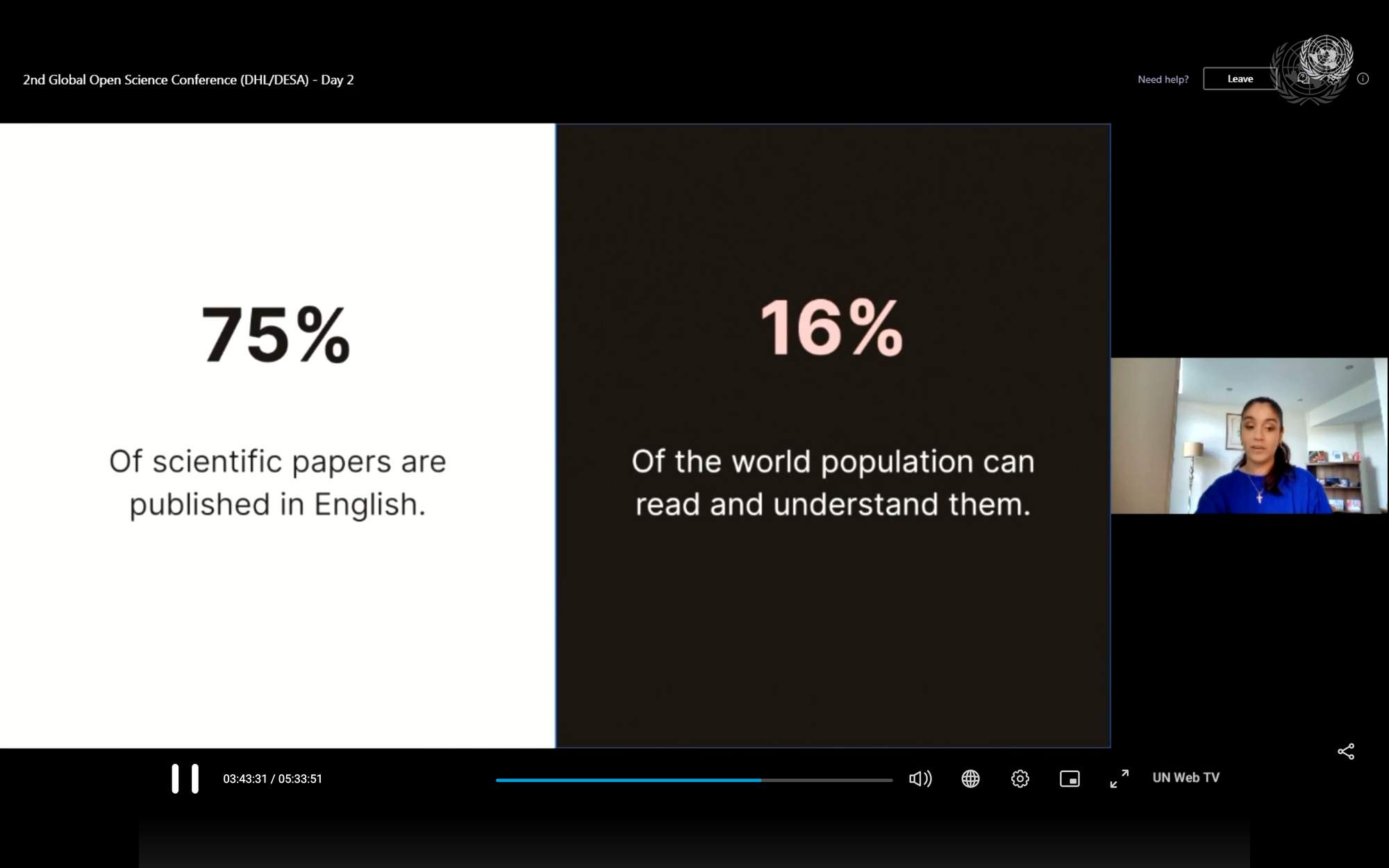

There are around 7.8 billion people in the world, and only about 1.3 billion of them speak english. 75% scientific papers are published in English. Solo 16% de las personas puede leerlos y entenderlos. English is not my first language, and the same is true for lots of researchers out there that want to contribute to science, but they can’t, because they don’t speak the “lingua franca” of the scientific community. By translating my work to spanish, I can help lower the language barriers that prevent a subgroup of researchers whose mother tongue is not english from being part of the conversation. This, combined with opening up my research methods, fosters reproducibility. In the future, I hope someone with the similar problems I faced can build upon my experience working in the open, share their work openly as well, and feed the chain in ways that make open science the norm.

Open science has been very good for the pandemic because it enabled us to research faster, and much of it has been open, but that does not mean the research's outcomes have been equally distributed. I came here to say and show how we can help solve COVID & climate fairly and equitably by designing open thoughtfully. To be able to apply lessons learned from Covid to climate change, the movement needs to work in ensuring that those who have the important questions can access and produce research, and transform it into real world impact for the people they care about.

Today I’ve tried to use my life story as a lens to prove that being open is not always the same as being fair and equitable. But I’m not saying that open could never be fair and equitable, because truth be told, I honestly think that one day it could be.

Thanks so much to the UN for inviting me, it’s been an honor to come back.